The Last Will and Testament of Elizabeth Pearson

We are grateful to Beth Hampson who discovered this Will and other documents dating from the end of the 1600s which sheds light on early Sunderland Point.

As there is much interesting material, we have divided it into two articles.

This first centres on Elizabeth’s Will. Next time will be on the inventory taken on the death of her husband Robert.

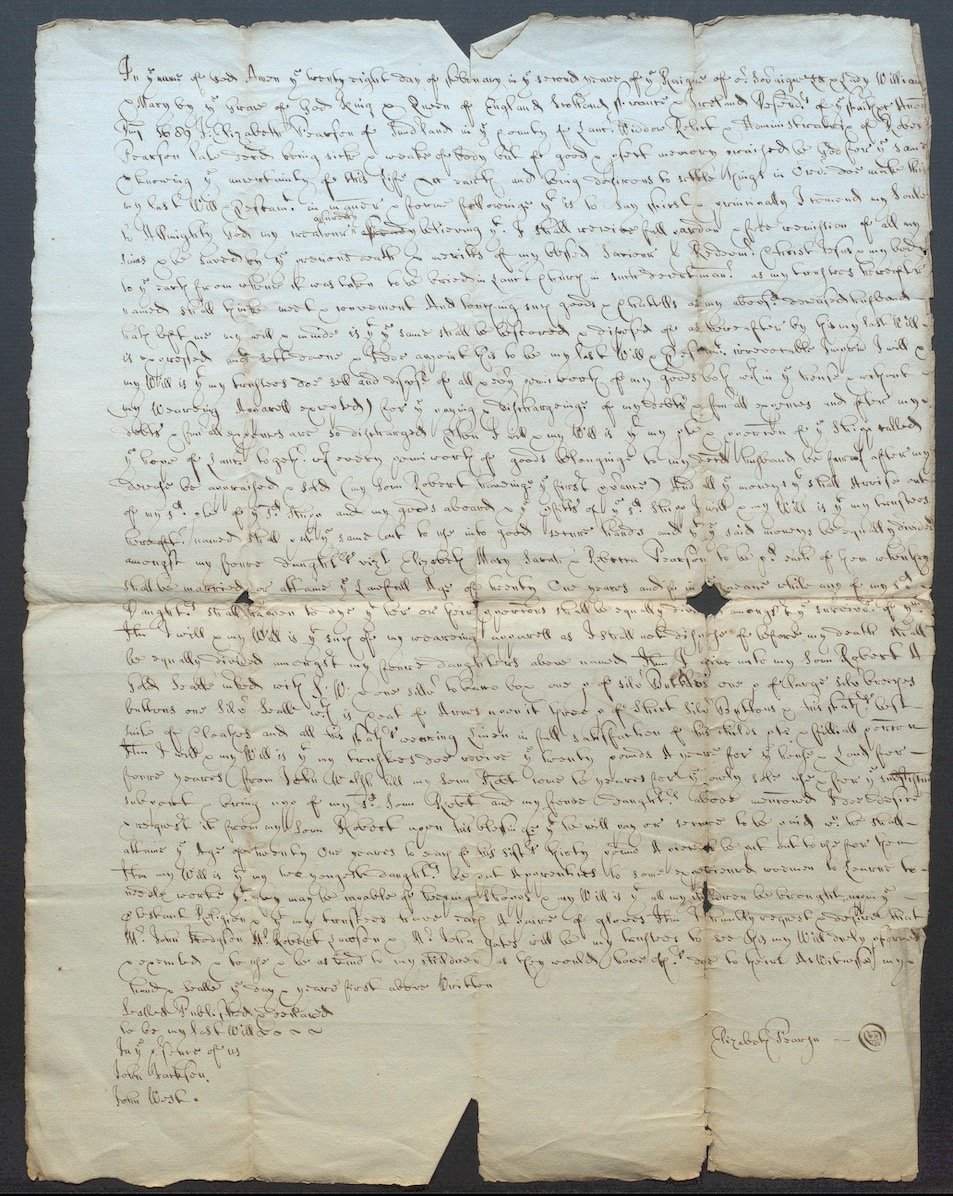

The last will and testament of Elizabeth Pearson: Courtesy Lancashire Archives

This document – illegible to the modern reader – holds important clues to the origins of Sunderland Point. At the same time, the Will contains the heart-breaking last wishes of a mother for her five young children knowing she had reached the end of her life.

The will is dated February 8th, 1689, and within a few weeks Elizabeth would be dead and laid to rest in Overton Churchyard. Her husband Robert Pearson had died two years earlier, his will has not yet been found, but we do have an inventory of his last belongings.

So, who are they and why so important to Sunderland Point?

Robert and Elizabeth Pearson

The Old Hall at Sunderland Point: Photo Alan Smith

This is their home, which they had built.

The Grade 2 listed Old Hall (or Sunderland Hall) is our oldest dated (1683) and most attractive building. Historic England dates it from the late 17th century.

The attractive porch, bay window and canopy are later 19th century additions. When these modifications were made, the date stone, probably once over the main entrance, was moved to the north facing side of the house.

The date stone at the Old Hall

The clearly visible initials are for Robert and Elizabeth Pearson. When Hugh Cunliffe was gathering material for his history of the Point, Robert was a mystery, perhaps a merchant born in Overton.

From the recent discoveries, he emerges from the shadows as one of the first courageous sea captains to have made the perilous transatlantic voyage to North America. His name appears as an owner of the ship the Hope of Lancaster and as master mariner and investor.

The later development of warehouse buildings at the Point by the Lawson family was driven by the West Indies plantation trade of sugar, rum, and coffee, but at the beginning the first ships setting sail from the Lune in the late 1670s were bound for the colony of Virginia for tobacco.

Reading the Will

Researcher Kate Hurst kindly provided a ‘translation’ of the Will. The simple humanity of Elizabeth’s wishes for herself and family written three and half centuries ago can now be read with relative ease.

Coming to the last lines something very special is revealed.

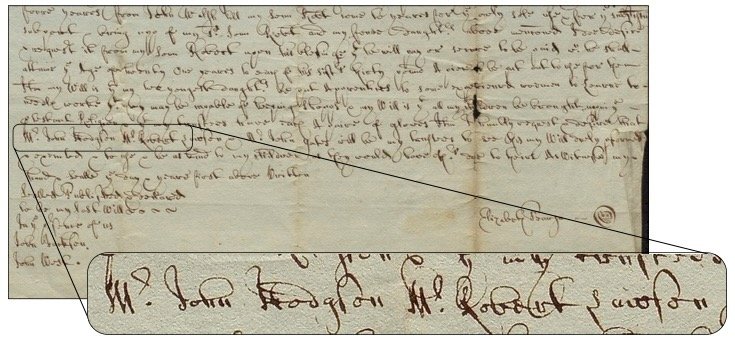

An extract from the Will. ‘Mr John Hodgson and Mr Robert Lawson’ have been highlighted: Graphic Paul Hatton.

Elizabeth has written ‘I humbly request, and desire Mr John Hodgson, Mr Robert Lawson, and Mr John Yates will be my trustees…and be kind to my children and they would doo to theirs’

This is an eye blinking moment. Robert Lawson was a famous Lancaster merchant and uncle of the Robert Lawson responsible for most early building work after c1715 at the Point. John Hodgson (to our embarrassment) was only vaguely known.

Searching history pages, it became evident that these two men were among the earliest, perhaps most significant of the entrepreneurial tradesmen turned adventuring merchants who established trading links with the plantation colonies in North America and later the West Indies.

They were both investors in Robert’s ship the ‘Hope of Lancaster.’

Commenting on the beginning of the economic transformation of the town, historian Nigel Dalziel writes:

‘Two local Merchants in particular John Hodgson and Robert Lawson showed the way’

And what a change it was. The population of Lancaster in the 1680s was around 2,000 – not much more than Overton, Middleton and Sunderland today – and it grew fourfold to over 8,500 a century later in the 1780s.

Two extraordinary men

In 1679, a voyage to Virginia - perhaps the second ever - was financed by John Hodgson and John Lawson (Robert’s father) who arranged for Robert Pearson’s ship The Hope of Lancaster to be loaded with a cargo of cloth, saddles, stockings, paper, and coal to exchange for tobacco.

In 1689, ten years later, John Hodgson, now with Robert Lawson, were the principal investors in the first West Indies voyage by the small 50-ton ship the Lambe.

John Hodgson

‘The greatest and most reputable merchant in Lancaster’.

Michael Mullet in ‘A History of Lancaster’

Hodgson was born in Ellel, near Galgate, and was originally a grocer and apothecary who formed a business partnership with his brother-in-law, a merchant from York. They cheaply acquired an old ship and at great risk achieved the first landing of tobacco direct from Virginia in 1677.

He was by some margin the leading merchant of the city, politically savvy as well as an entrepreneur, and he claimed special commercial privileges in ancient statues. Four times Mayor of Lancaster, he was first elected a Burgess in 1663, Chamberlain in 1664 and an Alderman from 1684.

He was owner, perhaps builder of the first Sugar House Lancaster to refine raw sugar and distill rum. He had interests in wines and spirits from France, Spain, Portugal and the Canary Islands. He was also involved in significant agricultural trade with Ireland.

But his principal interest was tobacco, and he even brought Peter Gourdin from Bristol to process the leaves. In 1679, the Hope of Lancaster returned from Virginia with over 70,000lbs of tobacco and in 1683, Robert Pearson returned with 50,000lbs, mostly for Hodgson.

A colourful, forceful man and keen social climber, he lived lavishly often beyond his considerable means. Eventually his expenditure was greater than his income and ambitions. His fall from grace was as spectacular as his riches. He died in the debtors’ prison, Lancaster Castle in about 1703.

Robert Lawson

Robert (of Lancaster) was born in 1652, the second son of eight children to John and Margaret Lawson. John, the founder of the dynasty, was a remarkable man in his own right. He was also a Lancaster tradesman, merchant and investor in the early voyages. He bought the Sugar House from John Hodgson and secured the right to open the first wharf on the river at Green Ayre in Lancaster.

John was also famously the merchant on St Leonard’s Street when George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, burst into his premises, chased by an angry mob throwing stones.

John Lawson had these crudely die-struck tokens during the shortage of farthings, possibly in the 1680s.

John Lawson’s ‘Farthings’: Courtesy Lancashire Archives

John died in 1689 ‘broke in a crazed and confused’ according to diarist William Stout - but never the less a wealthy man.

Robert quickly benefited from his father’s success. He is credited with successful investments - with John Hodgson and others - in Virginia tobacco, sugar, rum and cotton from the West Indies, wines and spirits from France and Portugal - and in the Baltic trade with voyages to Norway and Archangel in Russia.

In the 1690s, he and Hodgson provided war transport to Ireland in support of the campaigns of William of Orange.

Robert is also remembered when the boat he co-owned, the ‘Robert’, berthed at the Point, had its six guns confiscated by Jacobite rebels in 1715.

In his gossipy memoirs, William Stout records with a mixture of glee and incredulity that Robert Lawson lost substantially in the South Sea Bubble of 1720. Even so, by 1721 he was regarded as the wealthiest Quaker Merchant in Lancaster.

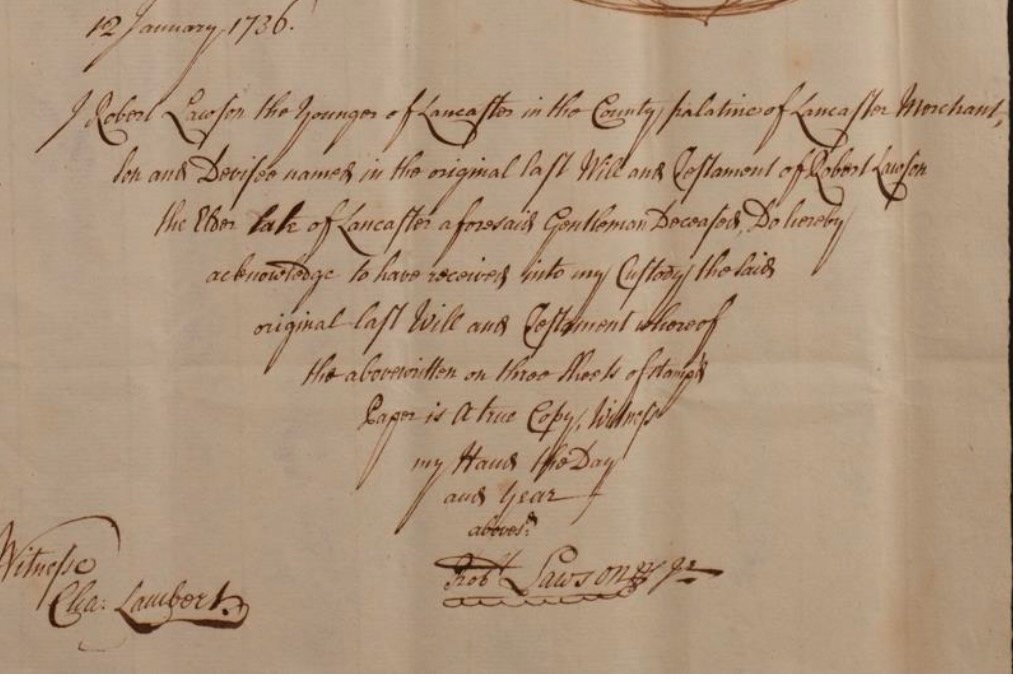

There is no full value of his estate on his death in 1737 but it must have been substantial. In his Will he bequeathed properties in Scotforth, Stodday, Heysham, Poulton (Morecambe) Oxcliffe and Heaton and in many other parishes and towns in Lancashire and in Yorkshire.

The tailpiece of Robert Lawson’s Will showing his signature: Courtesy Lancashire Archives.

The last Will and Testament of Elizabeth Pearson

Robert and Elizabeth had five children; we don’t know their ages but when Elizabeth died, they were all under 21. The provisions of the will suggest Robert, the only boy, was 16. His sisters, most likely listed in age order, were Elizabeth, Mary, Sarah and Rebecca.

In early February, 1689, terminally ill and knowing she had little time left to live, Elizabeth arranged for her will to be written. She had important things to settle, for herself, her son, and her daughters.

It would be a very cold heart not to be moved by her words.

After confirming the date she writes, ‘I Elizabeth Pearson of Sunderland, Widow…being sicke & weake of body but of good & perfect memory, praise be to God…do make this last will and testament’

Her first concern is for her mortal soul and burial.

‘Firstly, and principally commend my soule to Almighty God, my creator believing I shall receive full pardon…of my sins & be saved by the death of my blessed Saviour & Redeemer Jesus Christ. My body to ye earth…to be buried in fair church in decent manner…(as) thinke neat and convenient’

She instructs that her daughters sell all her domestic possessions and goods within the house (except her ‘wearing apparel’ which are to be shared between the daughters) to discharge any debts and pay the funeral expenses.

Next, Elizabeth instructs that her share of the ship the Hope of Lancaster together ‘with every (piece) worth left to her by Robert be appraised and sold’. Her son Robert to have the first quarter share.

The residue to be divided between the four daughters and to be given to them when they are married or reached the age of 21. If any were to die before this qualification, the share divided between the surviving daughters.

Special items belonging to her husband she identifies and bequeaths to Robert.

‘A gold seal inked with S.W. & one silver tobacco box, a pair of silver buckles, large silver dress buttons, one silver seal with a coat of arms upon it, and three pairs of silver shirt buttons.’

And ‘His fathers suite of cloathes and all his father’s wearing Linen’

The next provision appears to provide £20 a year for the living expenses of all the children for the next four years until Robert comes of age, at which time Elizabeth askes that he gives each of his sisters £30 (about £6,300 in today’s money).

Still thinking and worrying for the future for her daughters she writes:

‘It is my will my two youngest daughters be Apprentices to some experienced woman to learn needlework and be capable of keeping Shopps’

Next, and firmly (perhaps knowing with misgivings that Robert Lawson was a committed Quaker), Elizabeth says ‘It is my Will…all my children be brought up in ye Protestant Religion’

There is strange absence in the Will of any family members that might have been expected to take responsibilities for the children.

The last section appoints the trustees. For their services they are to be rewarded with a pair of gloves, and that heartfelt request.

‘Be as kind to my children and they have doo to theirs”

Many thanks again to Beth Hampson. Her excellent description of the Lawson Family is contained in the fourth of her books. Thanks to Kate Hurst for the ‘translation’ of the Will and to historian Margaret Robinson who confirmed details of the early voyages of Robert Pearson. Quotations are taken from ‘A History of Lancaster’ edited by Andrew White.

Next time, should be, ‘’The Inventory of Robert Pearson’