‘Brachium Forte’

Commemorative seat - Second Terrace

Between the fish house and the Old Hall is this partially hidden seat. A close look at the inscription on the brass shows it was placed here as a memorial to Philip and Constance (Connie) Taylor who were frequent holiday visitors to the Point.

Connie Taylor was one of three daughters of George Armstrong who held the tenancy of a house on Second Terrace (number 19) for 33 years. Recently, her daughter Rosemary visited the Point and kindly offered to send photos and write an article for us.

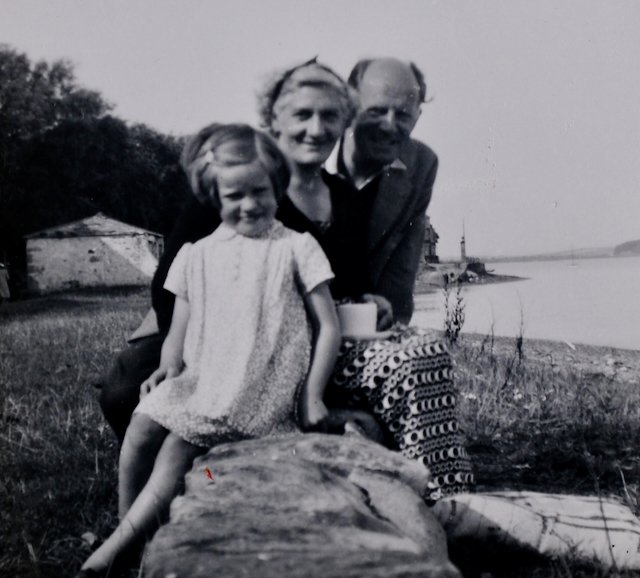

Rosemary, with her parents Connie and Philip Taylor on Second Terrace c1952: Collection Rosemary Thacker.

Rosemary:

From 1924 to 1957, my grandfather George Albert Armstrong (GAA) rented the cottage next to the Cotton Tree on Second Terrace (number 19)

George Armstrong at the front door of Brachium Forte (number 19): Collection Rosemary Thacker

GAA was born in 1875 in a back-to-back house in Leeds city centre, the son of an Irish immigrant. He trained as a teacher at St John’s College in York and began his career at a very tough Leeds city-centre school.

Later, in 1908 he was an elementary school Headmaster at Low Moor, south of Bradford. He moved to Bradford as Superintendent of the Boys’ Welfare Department of the Bradford Dyers’ Association. GAA believed passionately in summer holidays near the sea for the apprentices and established several camps.

For many years, George took his own family to Heysham for a month in the summer. But what he really wanted was a permanent cottage where they would go at anytime. Then they heard about Sunderland Point.

He described their first visit in the St John’s magazine:

Our first picnic there was quite unique, for we learned comings and goings to that locality would always be regulated by the ebb and flow of the tide.

We were advised how to get there and decided to arrive at the sand road before the tide was due to cover it. This was the original plan, but during the morning the actual happenings took an altogether different turn. There were no buses running to Overton in those days and the journey from Heysham – a distance of about six miles – had to be accomplished on foot. “Women and children first”, said the men, who were commissioned to transport bags containing the luncheon. “Alas and alack”, it was a terribly hot, sunny day and half-way between Middleton and Overton we – the men – letting the advance party get well ahead, lay down in a cornfield and fell fast asleep.

When we eventually awoke, we collected our food parcels and hurried after our wives and children; but we knew to our disgust that the time was long past when we should have been well over the causeway, and it would be another four hours before it would again be passable. Our wives greeted us with reproachful glances and appropriate sarcastic remarks about our reprehensible conduct. To make things worse for me personally, it was maliciously recalled that I had boastfully challenged one boy to hurry along in case I arrived at Overton first. This irrepressible young urchin commenced to recount to the party the ludicrous story of “The Hare and the Tortoise”, explaining with great glee that he was the Tortoise and I was undoubtedly the foolish Hare.

After a regretful committee meeting with those ladies of the party who would condescend to speak with us, it was decided to call it a day and retrace our footsteps via Overton and Middleton. We had no sooner come to this decision than a wonderful thing happened. A woman rapidly approached us and asked if “the tide was on the road.” On being informed of this sorrowful fact she quite calmly remarked, “Oh well, I must go over the fields then, I have to be at Sunderland Point in half an hour,” “Can we come with you, my pretty maid?” said the humourist of the party. “No”, she said, “for I am in a great hurry.” However, we eventually compromised and it was arranged that we who had previously lagged behind should now for our sins be commissioned to hurry over the fields with our welcome guide, and the rest, including the children, would follow later.

The way over the fields proved rather an exciting affair. It commenced with a cart road, then a hole in a wall took us along the side of a turnip field, through a cornfield which was crossed diagonally, then through various meadows, across several wooden bridges which covered deep dykes and so on. Halfway on our journey I and the small boy previously mentioned were the only companions of our quickly moving guide, who wickedly murmured that the Hare and the Tortoise were evidently the only survivors. In order that those who were coming after us might follow the scent, we decided to turn proceedings into a paper chase and my morning paper became small pieces which were profusely scattered at every stile.

Second Terrace from the river: Collection Rosemary Thacker

GAA also described a visit in 1924:

After a while a visitor came along with a bucket. I was at once all attention owing to the fact that he was wearing a York St John’s College blazer – green with bright yellow trimmings. It so happened that I was attired similarly. On my pocket were the figures 1895-96; on his were embroidered 1914-15. It transpired that he rented a cottage on a yearly tenancy and came to SP for all his vacations.

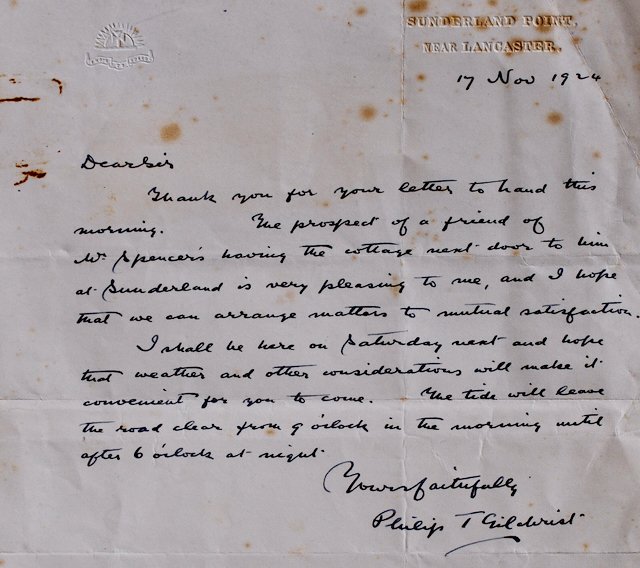

This Mr Spencer told GAA that the next-door cottage would be available from November, so he made enquiries and was invited to visit.

Letter of invitation from Philip T Gilchrist: Collection Rosemary Thacker

The weather was dreadful, but my grandmother was still keen which clinched the matter. GAA called the cottage Brachium Forte (Latin. arm & strong). For 30 years he and my grandmother Rosina, and their daughters Audrey, Daisy and Connie, spent holidays every year at Sunderland Point.

Later our father Philip Taylor, my mother, sister Gill and myself, went at least once every year. We lost the tenancy after Grandpa died in 1956. My parents would have gladly paid an increased rent, but the cottage was needed by a fisherman.

Connie, Rosy on Rosina’s knee, Gill, Audrey, Daisy and GAA

Audrey was very friendly in Bradford with Marjorie Womersley who later lived on First Terrace. They shared a love of embroidery. Marjorie’s father was a mill owner in Pudsey. I believe his sister married an SP fisherman (Gerard Bagot). Once Connie and Daisy started at Leeds University, they invited fellow students. My mother told me groups of these friends would cycle over from Leeds.

Margorie Womersley on left, Daisy centre (in Leeds University blazer) and unknown woman to the right inside Brachium Forte. Collection Rosemary Thacker.

Two of these students (possibly on the photos) were brothers Laurence and Wilfred Flather who were training to be doctors. They were also originally from Low Moor. Wilfred became an ophthalmic surgeon in Lancaster, Laurie a GP in Heysham. I have a letter he wrote to Connie congratulating her on her degree in 1928. He had just “ploughed” one of his medical papers and had “to take the whole bally lot again.”

Student friends with Connie seated on the ground in front: Collection Rosemary Thacker.

I believe there was a good social life on SP in the 20s and 30s with picnics, cricket matches and boat trips etc. George bought his three girls a car which Audrey and Connie drove on condition he would be chauffeured when needed. This made the journey and trips to dances and the cinema easy. All three girls were keen dancers. (Marjorie joined their first car trip to London. My mother managed to get the bumper wrapped round a bus in Piccadilly Circus.)

At the back Audrey Armstrong, fiancé Teddy Bottomley and Connie. In front, Daisy, GAA and his wife Rosina.

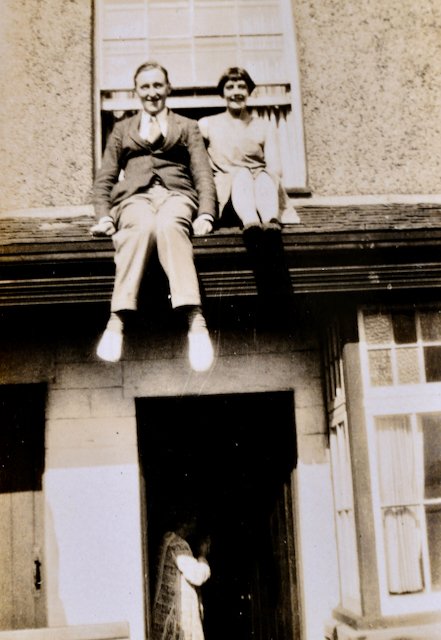

Daisy and friend on roof of Brachium Forte: Collection Rosemary Thacker.

GAA wrote this from SP in 1941:

The guns at the Point and at Barrow were engaging the enemy planes for about 4 hours. Then the armed ships in Heysham Harbour had a go. Finally, a destroyer in the Bay had a terrific shot loud enough to awaken the dead in Overton churchyard. It settled the issue because after that we had peace. There are about 200 artillery at SP in huts on the West Shore fields. The salmon fleet are only allowed out in daylight and then under certain conditions – they have to fly a certain coloured flag each day. They are getting a good price for it. I am trying to smoke less for several reasons. At one time I seriously thought of giving up altogether, but Mother said this was unpatriotic, so I continue to help the Government’s finances.

After the War, my parents had a different set of friends. I know they played Bridge with Peter Hall and his wife. Peter gave us lunch on my mother’s last visit to the Point. My father, who was the Headmaster at Malton Grammar School in Yorkshire, loved the peace of the Point. He would read and paint, but rarely finished a picture. However, my sister and I have one complete painting each.

Rosemary as baby with sister Gill in 1948: Collection Rosemary Thacker.

I was only eight when we lost the cottage, but my memories are very clear. I still feel the excitement of turning the corner at Overton and seeing the tidal road stretch across the mud. The front room of Brachium Forte had a frieze of SP scenes and ships round the top of the wall. It was said to be painted by a sea captain. Is it still there?

Brachium Forte and Pebble Beach Cottage (19 & 18) c1950: Collection Rosemary Thacker.

The lavatory was an earth closet down the garden. Gill remembers the clanging down the side passage made by the men who emptied the pan. I can still smell the milky odour in the cold dairy behind us when I was sent to fetch the metal milk can. Before bed-time Gill would take me up the Lane to jump the dykes on the west shore. Sea thrift and a small white flower bloomed there. We both still call it “SP moss” in our gardens.

Bert Smith sometimes took me in his boat towards Glasson Dock or out on the sand at low tide to dig for worms. Once an American came with us. He would not heed the warnings about sinking sand and had to be pulled out, which was frightening.

Bert Smith, Fisherman c1950: Collection Rosemary Thacker

Boat trip with Bert Smith (in cap), Philip Taylor in front with assorted children. Mavis Smith next to Bert: Collection Rosemary Thacker.

I was given coins to buy Smith’s crisps (with the salt bag) and dandelion and burdock from Townley’s front room (Number 16). Unknown to my parents I once drank so much that we had a long and ultimately pointless trip to Lancaster hospital, thinking I had an appendicitis.

Most of all I remember playing for hour after hour by myself on the path between the terraces and on the stile step.

We took Connie to SP a couple of times in the 1990s with my husband and children. Marjorie Womersley gave us tea and they reminisced. She still had several embroideries of Audrey’s on the walls. On a later visit she proudly showed me the bowl presented to her by the Embroiderers’ Guild. When the cotton tree blew down, Marjorie gave me her slice of the branch because she thought it meant more to me.

After my mother died aged 96 years in 2004, Peter Gilchrist planted a silver birch for us in his millennium wood. Then he arranged the installation of the bench on which we have placed a plaque in memory of our parents. It is along the lane to the Hall overlooking the estuary and the distant hills. It contains a phrase from my father’s favourite poet, A E Housman, about nostalgia and old age: “those blue remembered hills.”

Rosy Thacker nee Taylor

The brass plate on the memorial seat

A draft of this article was shown to Gill, Rosemary’s older sister, and she has added these vivid memories.

There were always white lilies decorating the church at Easter. The village children used to hard boil eggs and then decorate them using natural ingredients - dandelion leaves made them a yellowish orange. We rolled them down the slope near Sambo’s grave, to see whose cracked open the last.

The plaster on the inside walls of the front room in Brachium Forte must have been mixed with sea water. The walls sweated in certain types of weather and drops ran down them.

The only lights we had were candles and oil lamps which my grandpa used to trim. Halfway up the stairs was a shelf which held my grandma’s collection of Agatha Christie books which I read each year from an early age. I still love detective stories.

My most vivid memory is of the summer harvesting of the dried hay sheaves from the west meadows. The children could walk up there and then ride back on top of the load.

Standing at the front of the huge cart was Harry (Birkett) the farmer driving the horses. To me he looked like the god Apollo, always sunburnt and with his mop of golden hair. When we went to the farm in the morning to collect our milk in the metal gill jug, his wife Elsie measured it out. I thought she was very pretty.

A wartime photo of Elsie Birkett (nee Gardner): Collection Rosemary Lawn

When I think of SP now, the wonder of it all was the fact that I could wander everywhere at will in such a beautiful place, a lot of the time completely alone. To me, those holidays spent at Sunderland Point are one of my most treasured memories.

We greatly thank Rosemary and Gill for this wonderful and nostalgic article.